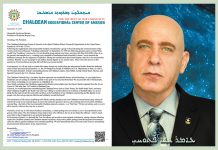

The Indigenous Chaldeans are the Living Seeds of Mesopotamia.” ~ Dr. Amer H. Fatuhi

First, I would like to clarify that the main goal of this brief study is to work toward halting the non-stop bloodshed against Chaldeans (the Indigenous Mesopotamians) and to condemn racial discrimination, demographic changes, and eradication attempts that Chaldeans face in their ancestral homeland, Iraq—especially the modern waves of persecution since 1966, which have intensified in cruelty and violence after the regime change in 2003 up to this very day. For this reason, achieving justice by recognizing Chaldeans in the Iraqi Constitution as the indigenous people of Iraq could play a crucial role in ensuring Chaldean continued survival in our homeland.

Secondly, it is worth noting that from the Achaemenid and Sassanid occupations, through the Arab Islamic conquest, the Mongol, Ottoman, and Safavid massacres, the so-called Islamic Caliphate (ISIS), and the religious and chauvinistic Iraqi regimes after 2003—most of which follow Iran’s Wilayat al-Faqih system (guardianship of the jurist)—persecutions, demographic changes, and genocides against the Chaldeans have never ceased. These crimes appear in direct and brutal forms, as well as in indirect forms disguised by fake “democracy,” hollow promises of openness to the international community, and deceptive claims of equality.

The truth is, there is nothing new for the Chaldeans. Since the fall of Babylon through the trick of diverting the Euphrates River executed by Gobryas, the traitor of the Babylonian mountain brigade in 539 B.C., the Chaldeans remained vigilant, ready to revolt and strike against the Persian invaders. Their chance came seventeen years later, in October 522 B.C., when Nebuchadnezzar III (Nidintu-Bêl) rose up in Babylon, gathering Chaldean rebels around him and proclaiming himself a descendant of Nebuchadnezzar’s youngest daughter, the wife of Nabonidus. Yet, King Darius I himself, commanding the vast armies of the Achaemenid Empire at its height, crushed the Babylonian revolt in December 521 B.C. Even though they lost, the Chaldeans realized there was still hope one day to expel the Persian occupiers.

In August 521 B.C., the Babylonians chose Nebuchadnezzar IV (Arakha Bar Kledita) as their king and launched another revolt, in which the Chaldeans initially defeated the Persian occupying forces. But once again, Darius sent a massive army that crushed the rebellion, retook the city, and executed the king who had fought to the last breath with his small army. The Persians impaled the king’s body, along with his soldiers (both dead and alive), on stakes inside the city to instill terror among the Chaldeans and break the spirit and morale of the Babylonian resistance.

Yet such brutality did not frighten Chaldeans nor stop them from rising against Persia. In late July 482 B.C., Bêl-shimanni raised a small army and took the Babylonian throne in August, but he could not withstand the massive Persian army of Xerxes I. To protect Babylon from destruction, he withdrew to Borsippa and allied with the powerful Chaldean king Shamash-eriba (Shumi-Raba), who also revolted. Together, they managed to expel the Persians from greater Babylonia (Mesopotamia).

In September 482 B.C., Shamash-eriba defeated Zopyrus, the Persian governor of Babylon and representative of Xerxes I, and reclaimed Babylon. The enraged Xerxes, determined to destroy Babylon once and for all, dispatched his brother-in-law and general Megabysus at the head of an army so vast that historical records claim its front ranks stood before Babylon’s walls while its rear extended all the way to Persepolis. The Persians crushed the Babylonian revolt with extreme savagery: they destroyed the Tower of Babel (Etemenanki), demolished the great temple of Marduk (Esagila), looted and burned much of the city, and carried off the golden jewel-encrusted statue of Marduk (Asallu ḫi) to Persepolis, where it was melted in a ritual to ensure Babylon would never rise again. Once again, the Persians impaled more than 3,000 Chaldean patriotic rebels on or around October 6, 482 B.C. This tragedy marked the end of native rule in ancient Iraq and the close of Chaldean-Babylonian aspirations for independence.

When the Achaemenids were finally overthrown by the Macedonians in 331 B.C., Babylon breathed relief. Alexander the Great, fascinated by Babylon’s grandeur, planned to make it his world capital. But death took him in Babylon—in Nebuchadnezzar’s palace chamber, surrounded by Marduk’s priests—on June 10, 323 B.C. After Alexander’s empire was divided, Seleucus I Nicator founded the Seleucid dynasty in Babylon, later building a new capital, Seleucia, in the ancient Chaldean city of Upi/Opis (near modern al-Mada’in). In 125 B.C., the Parthian Persians took Mesopotamia, beginning a new phase of harsh persecutions. Their Zoroastrian state viewed Chaldeans—who had accepted Christianity—as a threat. The Chaldeans endured bitter oppression for centuries, especially during the Forty-Year Persecution (340–381 A.D.) under Shapur II, followed by further massacres under Ardashir I (379–383), Bahram IV (420–438), and Yazdegerd II (438–457), lasting 64 continuous years.

By the 5th century, many Chaldean Christians of Mesopotamia adopted the Nestorian doctrine. Suffering under Persian oppression, they mistakenly viewed the Arabs, whose new religion seemed to them a Judeo-Christian sect influenced by Ebionite Christianity, as potential liberators. The Chaldeans aided the Arabs in battles against the Persians, including at al-Qadisiyyah. But soon after, the conquerors turned against the Chaldeans. The occupiers, Muslim leaders, imposed heavy Jizya (religious tax), insulted, threatened, and demeaned Chaldean Christians with degrading names like Nabateans (“peasants”) or ‘Ulooj (“infidels”). Those unable to pay faced conversion or execution, with their wealth and women taken by the conquerors. Many families converted under duress; others fled to the mountainous regions and near Nineveh’s Chaldean villages.

Under the Umayyads, especially during Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (685–705), Arabization policies intensified. His governor, al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, banned the Chaldean language in writing and speech, closed church schools, and cut the people off from their language, culture, and history education.

During the Abbasid era, Chaldeans suffered horrific persecution. The Caliph al-Mahdi (775–785) humiliated Christians in Baghdad. Caliph Al-Mutawakkil (846–861), notorious for his cruelty, imposed the infamous Pact of Umar laws: forcing Christian women to wear veils and humiliating robes, banning Christians from horseback riding, desecrating cemeteries, destroying churches and monasteries, converting unfinished churches into mosques, and forbidding Christian children from attending public schools. He even ordered demonic wooden signs hung on Christian homes, and forced men to brand their foreheads with degrading marks (demonic tattoos). Such humiliations continued under al-Muqtadir (908–932) and al-Qadir (991–1031), with massacres of innocent Chaldeans.

In the Mongol era, waves of massacres and persecutions drove many Chaldeans north. Ghazan Khan’s minister, the wicked Nawruz, decreed church demolitions, banned Christian rites, seized property, and killed Chaldean leaders. Later Mongol rulers continued atrocities, including forced castration and blinding of those who refused to convert to Islam. Timur (Tamerlane) carried out mass slaughters, forcing Chaldeans to flee to northern Mesopotamia (Nineveh Plains and Hakkari mountains).

Furthermore, under the Turkmen dynasties (Aq Qoyunlu and Qara Qoyunlu), illiteracy and fanaticism fueled further massacres by Safavid and other zealots, leading to the near disappearance of Chaldeans from central and southern Iraq, except Mosul and its surroundings. See: Ghanimah, Yousif Rizq-Alla, Jews of Iraq, Nuzhat al-Mushtaq in the History of the Jews of Iraq, Baghdad, 1922

During Ottoman rule, the empire brought in Kurdish Sunni tribes, whose continued massacres from 1515 onward seized hundreds of Chaldean villages in northern Iraq. Thirteen major Kurdish massacres and genocides forced reverse migrations: Chaldeans moved back into Arab-majority areas like Baghdad, Mosul, Basra, and Maysan, which were their ancestral lands before the Muslim conquests.

However, that temporary safety vanished again in modern times: under King Ghazi (1933–1939), anti-Christian, Arabist, and Islamist slogans intensified, worsened later by Gamal Abdel Nasser’s pan-Arabism. His Egyptian Constitutional article, “Islam is the religion of the state,” inspired Iraqi Ba‘athists to copycat this article and apply it in the Iraqi Constitution, which institutionalized discrimination. Persecutions under Abd al-Salam Arif spurred mass Chaldean emigration in the 1960s to the U.S., Australia, and Europe. Later waves followed the Gulf War and the 2004 “Bloody Sunday” church bombings in Baghdad and Mosul.

In 2015, Chaldean Christians of Iraq and Syrian Christian Syriacs, as well as Yazidis and other non-Muslims, suffered persecutions and massacres under ISIS—a tragedy echoing the Ottoman Sayfo genocide of 1915, which killed over 1.5 million Armenians, 350,000 Greeks, and more than 500,000 Chaldeans of Mesopotamia and Syrian Syriacs. This same discriminatory, Islamist mindset still dominates Middle Eastern regimes that falsely claim democracy and moderation, contradicting Iraq’s discriminatory constitution.

Because of centuries of massacres and genocides—from 482 B.C. to the 21st century—Chaldean political parties, organizations, and activists declared October 6 an official Chaldean Martyr Day in 2013, honoring all Chaldean martyrs who defended their name and dignity, as affirmed by the Bible: “Babylon, the jewel of kingdoms, the pride and glory of the Chaldeans” (Isaiah). This date also marks the turning point: from 4,818 years of Chaldean dominance in Mesopotamia to 2,506 years of foreign rule.

The commemoration of Chaldean Martyr Day on October 6th each year is not only meant to express our respect, pride, and remembrance of the sacrifices of our Chaldean ancestors who were martyred defending the Chaldean name throughout our long history. Rather, Chaldean Martyr Day is also an occasion to keep the sacrifices of our Chaldean forefathers alive in our minds, a reminder of the rich heritage of our Chaldean nation and the enduring legacy of its diehard sons and daughters who refuse to silently perish in the dark.

It is also an affirmation of the need to secure the proper conditions for new generations to carry the torch of Chaldean civilization and to provide guarantees for a better future for Chaldeans in the face of any form of threat, terrorism, or persecution.

As indigenous Iraqis—who first codified law, order, justice, and human rights—Chaldeans call for the removal of the discriminatory constitutional clause declaring Islam the religion of the state. Iraq is a homeland, not a mosque. The constitution must also explicitly recognize Chaldeans as indigenous Iraqis. Until then, the United Nations Security Council and the UN Indigenous Peoples’ Council must do their part to protect Chaldeans, the most ancient living nation on earth, from extinction. ~ Jeremiah 5:15

It is so crucial to highlight that, the Zoroastrian Persians, the Muslim Arabs, the Ottomans, the Mongols, the Seljuks, the Safavid Persians, the Mamluks, the Azerbaijani Turkmens, the Kurds, and other Muslim invaders tried relentlessly to suppress, persecute, kill, and bury the Indegigenous Chaldeans—ignorant of the fact that the diehard Chaldeans, resistant to extinction, are the living seeds of Mesopotamian.

Thus, regardless of the brutality and savagery practiced by invaders and occupiers, and despite all their efforts to eradicate Chaldeans and uproot us from our ancestral homeland, and even though our percentage in our homeland (Iraq) has declined from 95% in the mid-7th century AD—during the barbaric Muslim invasion of Mesopotamia—to nearly 0.01% after 2003, Chaldeans, despite all hardships and challenges, and despite all the inhumane and evil practices against the Chaldeans, the (indigenous Iraqis), after every ordeal, sprout again and flourish once more in the soil of our ancestral homeland in which the invaders attempt to bury us—unaware or deliberately ignoring the fact that Chaldeans are the salt of Iraq’s soil, the living seeds of Mesopotamia (the land of the Garden of Eden), and that just as Jesus Christ rose from death and conquered death with life, we too shall rise and shine again!

For further reading, see Dr. Amer Hanna Fatuhi’s publications below:

Chaldeans Since the Early Beginning of Time, (Arabic edition), US 2004; Iraq 2008

The Untold Story of Native Iraqis, Chaldean Mesopotamians 5300 BC-Present, US 2012

Chaldean Legacy, US, 2021

The Jews of Babylon, Past & Present, US 2023