Chaldean Nation Syndicated News

Publisher: Dr. Strahil V. Panayotov, BabMed Project, Free University Berlin.

Fumigation is a term for healing through the power of smoke. It is a wide-spread therapy in many traditional healing systems and it was also used in Ancient Mesopotamia.

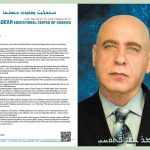

Through fumigation the Babylonian medical practitioner could heal different illnesses: depression, epilepsy, troubles with the ears and the eyes, or even hemorrhoids. A solution of potent drugs produced the smoke. To produce each blend, different substances were mixed with plant’s sap and/or oil in special vessels [fig. 1].

Then, in order to produce the smoke, the medical practitioner poured out this mixture over hot cinders. Afterwards the sick body parts were exposed to the smoke. Fumigation has a quick-acting physical effect, especially when the smoke is inhaled. This is due to the swift way of administering drugs that is much faster then internal medication. Furthermore, using aromatics for fumigation (Babylonian medical practitioners often mentioned conifers, and especially their pleasant smell) most likely induced psychological effects, which are comparable to aromatherapy.

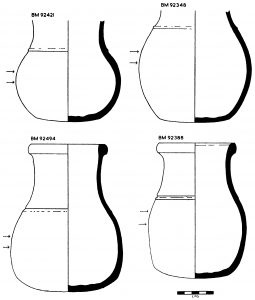

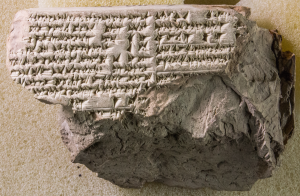

Well, this is only one kind of fumigation. Yet, when a demon had to be expelled stinky and pungent fumigants came into play, as it is the case for the translated recipe below. It dates to the time around or shortly after the death of Alexander the Great, at the end of the 4th century BC. The cuneiform tablet was found in ancient Uruk – nowadays in South Iraq. The fumigatory mixture is extraordinarily interesting. It was prepared to cure epilepsy as well as the demonic attacks causing it. The main ingredient consists of parts of the head of a dead young male goat. The whole ritual process could be reconstructed as follows: the medical practitioner recited a spell ‘O, evil, evil’ in the both ears of a young male goat. Perhaps, in this way the flesh of the young male goat was magically activated to produce the potent substance, needed to fumigate out the demonic presence. Then the practitioner slaughtered the young male goat. He took different parts of the head of the young male goat mixed them with naphtha, saps of plants, oils and plants. He prepared a solution, which he first gave to the patient to drink and eat. Then, with that very same mixture, the body of the patient was anointed and at the end he was fumigated [fig 2].

TRANSCRIPTION:

If [ep]ilepsy, Lugalurra-epilepsy-demon, Hand of God, Hand of Goddess befall a man: in order to remove it – it’s ritual: you take a young male goat, you recite [in] its right and left [e]ar the incantation ‘Oh, evil, evil’, (and) you slaughter (it). You take blood of the eye, the pupil of the eye, the covering-tissue of the depressions of the head and the neck, the dark fluid of his two eyes, naphtha, fish oil, cedar blood, maštakal[1]-plant, seed of maštakal-plant, owl blood, skin of a qiššû-cucumber,[2] tendril of qiššû-cucumber – pure fumigants, taramuš-lupine plant, imhur-līm[3]-plant, imhur-ešrā[4]-plant, [you (crush and?) m]ix [(them) together.] He shall eat it (and) drink it, you anoint him and fumigate him over cinders, and then he will get better. [14 drugs for] fumigation with a young male goat.

The peculiar substances mentioned in this recipe have certainly also symbolic significance, which, we may assume, sometimes go along with the chemical usefulness of the substances, since Babylonian traditional medicine was based on empirical experiments that had lasted for thousands of years. Some of the substances, such as ‘owl blood,’ were alternative names for drugs and some were not. We know this because some passages of the text were discussed in ancient commentary, which helped healers understand the extraordinary substances better.

Further reading:

Frahm, E. 2011. Babylonian and Assyrian Text Commentaries, Origins of Interpretation. Münster: Ugarit.

Geller, M. 2010. Ancient Babylonian Medicine, Theory and Practice. Chichester (GB) & Malden, Mass: Wiley-Blackwell.

Labat, R. 1961. A propos de la fumigation dans la médecine assyrienne. Revue d’assyrologie et d’archéologie orientale 55: 152-153.

Stol, M. 1993. Epilepsy in Babylonia. Groningen: Styx.

Thureau-Dangin, F. 1922. Textes Cunéiformes VI. Tablettes d’Uruk. (TCL 6) Paris: Paul Geuthner.

Walker, C.B.F. 1980. Some Mesopotamian Inscribed Vessels. IRAQ 42: 84-86.

[1] Unknown plant used often for purification. Scholars often translate it as soapwort, which is not certain at all.

[2] Qiššû-cucumber, written dKu-ši ‘God Kušu’ is most probably syllabic secret writing of kuš8 =qiššû-cucumber. Suggestion is courtesy of Prof. Andrew George. Furthermore, the reading makes very good sense in the light of the fact that tillatu ‘tendril’ of dKu-ši was used. On the on hand, it is possible that the qiššû-cucumber could be deified; on the other the god Kušu could be symbolically represented by the qiššû-cucumber.

[3] The name means ‘it resists thousand (ailments)’.

[4] The name means ‘it resists twenty (ailments)’.