San Diego Jewish Press-Heritage, Aug. 23, 2002

By Donald H. Harrison

And He said unto him, I am the Lord, that brought thee out of Ur of the

Chaldees, to give thee this land to inherit it.– Genesis 15:7

Father Michael J. Bazzi remembers a time in Oak Park, Mich., prior to his

arrival in 1985 to be a pastor at the St. Peter Chaldean Catholic Church in

the Rancho San Diego area, when he broke up an argument between some

Chaldean and Jewish boys. The Chaldean boys complained that the Jewish boys had called them “camel jockeys” and asked why anyone would think that they had ever ridden a camel. Bazzi decided to explain to the Jewish boys exactly who Chaldeans were.

There are three verses in Genesis –11:28, 11:31, and 15:7 — that bespeak

Abraham’s nativity in Ur of the Chaldees. “Abraham was a Chaldean,” the

priest said. “Do you know what that makes you to each other? Cousins!”

Before his assignment in Oak Park, the Iraqi-born priest on one occasion was celebrating Mass in the Aramaic language in a church in Milwaukee, Wis. “There were hundreds of people at the Mass,” he recalled in an interview with Heritage.

“And when we came to the tradition that says Owhoever is not baptized,

please leave; this is only for Christians,’ guess what, all of a sudden I

discover that there is this rabbi with his wife and three children, and they

stood up to leave. I said, ODon’t! Sit down! This is an old tradition,’ and

(after the Mass) we came out and became friends. We shook hands, and he

said, OFather, you want to know the truth, I heard all the Mass in Aramaic

and something was burning in me, because this was our language too.'”

Bazzi told the visiting rabbi that there used to be Jewish villages near the

Iraqi town of Mosul — which was the Nineveh of the Bible — and that he

himself had grown up in Telkeppe, not far from there.

“I asked him if he spoke Aramaic, and he replied only for funeral prayers.

Then he whispered in my ear: ‘Do you realize, I don¹t understand many of

them?’ “The Kaddish prayer in Aramaic is just one inheritance from the language spoken by the Chaldeans, whose King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon sacked the First Temple in Jerusalem and had the Jewish leadership transported into captivity.

Father Bazzi now serves as pastor at a church in Rancho San Diego that

reflects the Chaldeans¹ Catholic religion and ancient past.

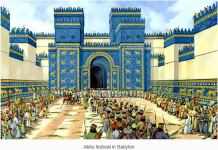

The stained-glass windows of the church depict episodes in the life and

death of Jesus — similar to what may be found in Catholic churches

throughout the world. Across the parking lot, however, stands a social hall

guarded by two fearsome figures from Chaldean mythology. Inside the hall

which on the day we visited was being set up for a wedding reception — are

numerous paintings recalling the glory that was Babylon¹s.

Earlier in the week, I had the opportunity to meet with a deacon of the

Chaldean Catholic Church. Our interview amplified on some of the

observations that Bazzi shared verbally and in writing, through the gift of

his book, Chaldeans: Present and Past.

The deacon was happy to answer every question, but he made one request of me. Please do not identify him by name, he asked, only by his position. He explained that with the United States possibly on the verge of war against Iraq, some people in the Arab community might consider it an act of betrayal for him to speak to a Jewish newspaper.

While the Chaldeans have their own language, they also speak Arabic, which is the official language of Iraq. St. Peter Chaldean Catholic Church offers separate Masses in each language.

The deacon told me that the name “Ur” is a form of the Chaldean word ura,

meaning “light,” similar to the Hebrew word ohr as in Ohr Shalom Synagogue — Light of Peace Synagogue. Although the name “Ur” can be found on a map of southern Iraq, to the inhabitants of that area the town is better known today as Mugayer — an Arabic word meaning bitumen, an asphalt-like substance often associated with oil fields.

³Where there is oil, there is natural gas,” said the deacon. “It’s possible

that ur — light — referred to fire, perhaps burning gas,” he theorized.

“Ur” also appears in the names of kings, such as Urnamu, as well as in the

names of towns, such as Urshalim. To Jews, the latter is better known as

Jerusalem, the deacon instructed.

There are many references to the Chaldeans in the Bible, especially in II

Kings, II Chronicles and the books of the prophets Ezra, Nehemiah, Job,

Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel and Habakkuk. The picture drawn of the

Chaldeans of pre-Christian times is one of fierce warriors who, because of

God¹s displeasure with the Jews, sacked Jerusalem and marched the Jewish

elite into Babylonian exile, which lasted from 587 BCE to 538 BCE.

The Babylonian emperor Nebuchadnezzar, like the Pharaoh in Genesis, depended upon a Jewish captive — Daniel — to interpret his troubling dreams.

The Chaldeans, like the Jews before them, suffered the displeasure of God,

who is quoted in Isaiah 47:5-6 as saying:Sit thou silent, and get thee into darkness, O daughter of the Chaldeans; for thou shalt no more be called the lady of the kingdoms. I was wroth with

my people. I have polluted mine inheritance, and given them into thine hand; thou didst shew them no mercy; upon the ancient hast thou very heavily laid the yoke.

The Persian King Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon and freed the Jews,

although some elected to remain. The Temple in Jerusalem was rebuilt and

rededicated in 515 BCE.

I also had occasion to meet with Sabah Sadik, a former editor of the Iraqi

newspaper Al Jumhuria (The Republic), who told me that as a Christian he

feels particularly uncomfortable with the destruction of the First Temple of

the Jews. “I don’t like Nebuchadnezzar,” he commented. “He killed many

people. “Any war is not right, any war at any time” responded the deacon during a conversation at the Chaldean Club, which meets in the Crystal Ballroom in El Cajon. “Any war, any captivity…”

After the Romans destroyed the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE, and Jews were again forced to leave the area, many found their way to the

still-flourishing Jewish community in Babylonia. Another wave of immigrants came to Babylonia after the unsuccessful Bar Kokhba revolt in 135 CE. Over the next two centuries, Jewish academicians in Babylon wrote commentaries on the Torah that were compiled into the Babylonian Talmud. A separate, smaller Talmud was composed in Jerusalem.

Meanwhile, the Chaldeans became fairly early converts to Christianity, a

religious belief that made them a minority group within the Persian Empire. Like Jews in other countries, Chaldeans found that as a minority group their fortunes could wax or wane depending on the political situation.

In his book, Father Bazzi wrote: “Prior to the conversion of the (Roman)

Emperor Constantine to Christianity (AD 313), the Romans actively persecuted Christians. The Persians, on the other hand, tolerated them because they were enemies of Rome. So while the Christians in Rome had to hide, their brothers and sisters in Mesopotamia (a Greek word for the area of the old Babylon, located between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers) were prosperous and well organized.”

After the emperor’s conversion and Rome’s defeat of the Persians, the

Byzantine Empire under Constantine began promulgating a series of

anti-Jewish laws. One forbade males to convert to Judaism. Constantine’s

son, Emperor Constantius, in 337 CE extended the ban to female converts and prohibited intermarriage between Christians and Jews. Thereafter, the

situation of the Jews changed for the good or the bad according to the

political leadership.

In the 5th Century, a split developed between the Pope in Rome and the

Church of the East — as the Catholics in the Byzantine Empire were then

known. Members of the Church of the East embraced the doctrine of

Nestorianism. In his book, Bazzi said the controversial doctrine “stressed

independence of the divine and human natures of Christ and in effect

suggested that they were really two persons loosely united by a moral union — that is, there was Christ the man and God the Son as a sort of Divine

counterpart.”

In the early part of the 7th Century, Persian forces reconquered much of

Asia Minor. Many Jews joined the Persians in the campaign against Rome and its anti-Jewish edicts. The Persians extended a measure of tolerance toward the Nestorians, on the grounds that they too differed with Rome, according to the deacon. He added that many people embraced the Nestorian church not because they felt passionately about its doctrines, but in order to ingratiate themselves with the Persians.

Later that century, the forces of Islam swept from the Arabian Peninsula

through Asia Minor, conquering all of Mesopotamia by 651 CE.

“In the beginning the Chaldeans accepted the Arabs because they were not as severe as the Persians,” the deacon told me. “The Persians used to kill

Christians by the thousands. When the Arabs came, the Chaldeans were happy, thinking they would be a good substitute for the Persians, but unfortunately they were not. Their slogan was Aslim Taslam, OSwitch to Islam and you will be saved.’ If not, you have to pay jiziya — extraordinarily high taxes. Imagine if I am making $10,000 a year, my taxes would be $12,000, so this forced people to choose Islam.

“But those who wanted to keep their religion, they went to the north,” where the topography is mountainous, the deacon said. “That is why most of the Christians of Iraq come from the north. People went there where it was not easy to catch them or force them to pay jiziya. … It is not a tax

actually, it’s more like buying your life.”

So matters remained for nearly a millenium, until the Patriarch of the

Church of the East made a profession of the Catholic faith before Pope

Julius III in 1553. However, Nestorianism subsequently reasserted itself.

Eventually, those church members who accepted the guidance of the Pope in Rome became known as members of the Chaldean Catholic Church. Those who remained independent became known as members of the Assyrian Church of the East.

“One people, two denominations,” said the deacon. Under Islamic rule in Iraq (a name possibly taken from the town named Uruk), Jews and Christians coexisted for centuries as minorities. Before the creation of Israel, both religions had five seats for a total of 10 in the

National Congress, according to the deacon.

“I used to have many Jewish friends in Telkeppe,” said the deacon. “I used

to go on Saturday, and I used to put on the lights for them. There was no

electricity, so I put on the furnace for them.” With the creation of the State of Israel, most Jews emigrated from Iraq,

although a tiny remnant remained.

Sometimes adversaries, sometimes friends, the Jews and Christians of Iraq

now are fellow refugees, with most of the Jews having gone to Israel and

many Christians having come to the United States.

Bazzi wrote that Dr. Joseph Gibran, a physician who came to San Diego to do research, was the first Chaldean to settle in this area. That was in

December of 1951. A trickle of immigrants followed over the next decade,

including Wadie P. Deddeh, who had come from Detroit to teach high school in Chula Vista. In 1966, Deddeh was elected as a state assemblyman, remaining in that office until 1982, when he was elected a state senator. He retired from elective office in 1993 following an unsuccessful bid for the U.S. Congress.

In 1964, Mar Paulus II Cheikho, the Chaldean Patriarch of Babylon, traveled

from Iraq to San Diego. There were only 12 Chaldean families here, Bazzi

reported. In 1973, Rev. Peter J. Kattoula, a Chaldean priest from Telkeppe,

was assigned as a pastor to San Diego’s growing Chaldean community.

In 1974, the Chaldean community purchased 5.09 acres near Rancho San Diego for the present St. Peter Chaldean Catholic Church. Approximately 260 Chaldean families lived in the area when the church was dedicated Sept. 10, 1983 by the Patriarch and by U.S. Chaldean Catholic Bishop Ibrahim N. Ibrahim. Bazzi was assigned to San Diego two years later and was promoted in 1986 to the position of co-pastor with Kattoula. Kattoula died the following year.

The church hall was opened in 1989, and in the following year the new

Chaldean Patriarch of Babylon, Raphael I Bidawid, visited the church on a

three-day visit. The community continued to grow, and in 1999 Sabri A.

Iskander was appointed as an assistant pastor to establish a new parish in

El Cajon that became St. Michael Chaldean Catholic Church. He became a full pastor in 2000, when St. Michael was established as an independent parish. How important is the growth of the San Diego area Chaldean community was signaled last month when Sarhad Yawsip Jammo was ordained as a bishop. Based at St. Peter’s, he now administers Chaldean Catholic affairs in the western United States.

Bazzi estimated that approximately 120,000 Chaldean Catholics were served in 14 parishes throughout the United States last year. These included five

parishes in metropolitan Detroit, where Chaldeans number approximately

100,000; two parishes in San Diego, where they number 15,000; and the

balance located in Turlock, Los Angeles, San Jose, the San Francisco Bay

area and Scottsdale, Ariz.